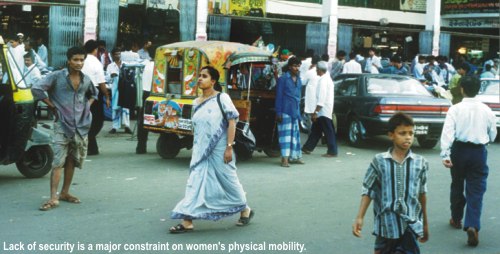

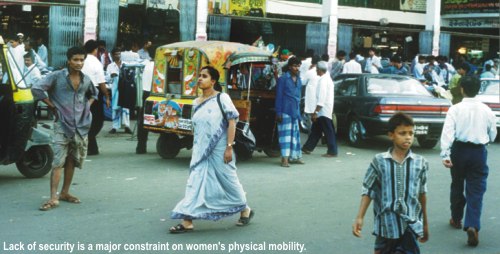

We cannot walk alone in the streets because it is not safe. We cannot work long hours because it will hamper our household duties. We cannot go abroad to study because what if we go astray? We cannot think our own thoughts, speak our minds or even breathe as freely as we would want to. For every step we take forward, we must go back a few steps more. It is not just physical immobility that constricts women's freedom but social prejudice and parochial state mechanisms that ensure that women go only so far, whether it is in terms of education, profession or merely as individuals with identities of their own. Social constraints are so strong that they even manage to make women believe that they are not entitled to freedoms equal to their male counterparts. Thus they give in to the conspiracy of setting limits to their freedom. Aasha Mehreen Amin, Kajalie Shehreen Islam

Srabonti Narmeen Ali and Elita Karim

While poor women have the least freedom in terms of how they will lead their lives, women from more privileged backgrounds, too, constantly run against blank walls at crucial points in their lives. Freedom is curtailed by depriving women of education or the ability to earn. So is there a way out? And what really is 'freedom' for a woman?

"To me, freedom means to do as I like without being made to feel guilty," says Shakila, a 29-year-old woman who has lived with double standards all her life. Although she went to school in the UK, coming from a wealthy but conservative family, she lead a very different life from her brother. She was made to go to an all-girls school and was not allowed to go out unchaperoned. Her father eventually brought her back to Bangladesh while her brother stayed on to complete his education and later pursued a career. In Dhaka she was not allowed to go back to school and had to take her O' and A'levels privately. "I was not allowed to go anywhere. If I got crank calls I would be severely reprimanded as if it was my fault," says Shakila.

Soon, like so many young women, Shakila had to get married, after which she found herself in yet another prison. Her husband's job took up most of his time and every night he would come home at 1 or 2 in the morning. "I had no life at all. My mother-in-law would frown every time I went out, and when I wanted to start a part-time job my husband just said no. I fought for a while but then backed off as I was too tired of the confrontations."

If Shakila had to do it all over again, she says, she would definitely have completed her education and taken up some profession. "Women must educate themselves and be financially independent before they commit to anybody. This will give them the grounds to fight for their rights after marriage."

Although her situation has not changed much -- she still is discouraged to work -- she is a much stronger woman because she has managed to overcome her feeling of helplessness. "I read a lot and this has kept me sane. I no longer try to please everyone at the cost of my peace of mind."

To Aneela Haque, CEO of her own company, Andes, and an established fashion designer, freedom means "to be myself just the way I am".

"Our religion always talks about 'women's freedom'," says Aneela. "But our present religious practice has a negative impact on women's freedom. Religious fanaticism has placed major constraints on women's freedom. Societal norms are based on such fanaticism so girl children grow up under different rules than boys."

"If I want to go somewhere far with my friends," says 24-year-old Aditi, a university student, "I need to do a lot of convincing for my parents to give me permission. Even if I want to go on a long drive, I will have to take someone with me."

Her brother, says Aditi, has it much easier, and can almost always get his way with their parents. "When I wanted to get a motorbike, my father wouldn't let me, because he didn't like it. But my brother managed to get his way."

Her brother, says Aditi, has it much easier, and can almost always get his way with their parents. "When I wanted to get a motorbike, my father wouldn't let me, because he didn't like it. But my brother managed to get his way."

"It's funny," she says, "how, as he grew older, he just assumed his right to the front seat of the car, something I never did or could."

Aditi wants to go abroad to pursue her higher studies, but her parents want her to get married first. "They're looking for suitors living in the countries I want to go to," she says.

"Our parents are wonderful," says Aditi, "and they take great care of us, but when it comes to daughters, somehow, it's as if they feel insecure for they could easily lose their respect in society because of us. It's like the duck and chicken. Men are like ducks -- whatever they do, when they come out of the water, they're dry. Women are like chickens; when they come out of the water, they're completely drenched."

While her brother will most probably go abroad for higher studies once he completes his HSC, and look after the family business when he returns, Aditi's own future remains uncertain. She too wants to go abroad, perhaps do a Ph.D.

"But will that be of any use here?" she asks. Even if she comes back, what will her life be like, she wonders. Will she live alone with her husband or move in with her in-laws? The decision will not be up to her.

In a society where a woman's ultimate goal is seen to be finding a husband and raise a family (hopefully more sons than daughters) and with her own biological clock ticking away, marriage is inevitable. For most women, marriage significantly places limits on her freedom, whether it is freedom to go out of the house or to earn her own income. But is marriage an absolute necessity?

"No, I don't think that either being married or having children are an absolute necessity for happiness," says Zara, a happy single at 34 who works for a human rights organisation. "Not everybody is cut out to be a parent, as is indicated by the number of children who grow up as difficult or traumatised adults because of bad parenting."

"For those who like children, but may not feel a biological urge to have a child, I am sick and tired of hearing them described as 'unnatural', particularly if they are women. There are many unwanted children in the world, and I think more people should consider adoption."

"Most women in our country are raised as weak and dependent," says Aneela Haque, "for such women, marriage is a necessity. Women with education, inner strength and determination can choose to be independent and single. It doesn't have to be a necessity."

Looking back on her life of 50 years, Parvin is more or less satisfied. Though she was under certain restrictions while living with her parents, during her married life, she has been relatively free. "I worked. I went out. I pretty much did as I wished," she says. "But then, I didn't really have to work nights or stay out late. Perhaps then there might have been problems."

A girl or woman is almost always dependent on a man in some form -- whether father, brother, husband or son. And her situation always depends on her having or not having such a man in her life. Many girls' futures become uncertain if their fathers pass away. They are pressured to get married earlier to reduce the burdens of the mother and other family members. Families with many daughters also feel the need to marry them off early, especially if the father is, say, old and approaching retirement.

Naila got married young and, until then, never quite thought about doing anything other than what her parents wanted.

"I didn't mind getting married," she says, "but I didn't realise that I would have to quit studying. I moved abroad with my husband and couldn't finish my Bachelors until I came back to Bangladesh some years later."

"I never really felt confident enough to work," says Naila. "Maybe if I had economic freedom, I would have felt more independent. Or perhaps if I lived in another country. For, in many countries, housewives are considered equal to working women and their contribution to the family and household is recognised as work, unlike in our country."

Forty years down the road, Tinni's life is not very different from that of Parvin's and Naila's. While living with her parents, she had her freedom, except for being allowed to go on class picnics and trips with friends. But after her father died, she was forced to marry her cousin.

"No one can say no to anything my uncle (her mother's eldest brother) says," says Tinni, now 23. So, when he wanted me to marry his son, my mother couldn't refuse, and I had to do it -- against my will."

A year into her marriage, while in her third year of university, Tinni had a baby daughter. Having a child has obviously brought on more responsibilities. "I might have to skip classes to look after my child."

"I am obviously not as free as my husband," she says. "He does as he pleases, goes out on business or for whatever reason, whether I want him to or not. I'm obviously not allowed to do that. Wherever I go, it's with my husband."

To many women, the dream of marriage is not one that coincides with reality. The acquisition of gold zari-threaded saris and heavy sets of jewellery, the smell of uptan on the day of the holud, the anticipation of starting a new life with that new someone, the concept of having and being a family unit -- all of this falls short when the more practical face of marriage rears its ugly head. Responsibilities come into play and all of a sudden the decision-making process does not involve only one person, but rather two.

Marriage is an institution which both the man and the woman have to adapt to and compromise in. There are certain things that singledom awards that married life does not allow. But the question is ,how much of that adapting and compromising affects a person's personal and professional growth?

Many women feel that they have had to compromise on their professional lives and their careers after marriage.

Shiuli was a 22-year-old who had graduated from a reputed private university in Dhaka and holds a degree in English Linguistics. She finally got married to her dream man, a young executive she had been going out with for some time. She was planning on applying for her Master's degree in the USA, train under a good linguist, work towards a Ph.D. and then return to work in Dhaka. Within a year, Shiuli gave birth to a baby boy. She decided to forgo going abroad and opted for a Master's degree in linguistics from the same private university from which she had done her undergraduate studies in Dhaka. She was about to register for the semester, when suddenly her two-month-old son got ill and she had to give up her dream of doing her Master's altogether.

Now, almost 25 years of age, Shiuli works at a nearby school as a Class 4 social studies teacher. She looks upon her dreams of being a university professor as a far away thought and sometimes dares to ask herself as to why she sacrificed her ambitions to fulfil her duties as a wife and mother, only because she is a woman.

Even in an age where women are encouraged to have a mind of their own and think of a future for themselves, their dreams usually stop with the thought of marriage. Over the centuries, the birth of girls has always been related to marriage, either positively or negatively. Even today, society seems to judge a woman by her marital status, no matter how successful she is in her career.

Twenty-year-old Farzana, an architecture major, is working part-time at a foreign company in Dhaka while pursuing full-time undergraduate studies. She dreams of having her own architectural firm in Dhaka one day, and plans to work on a Master's degree as soon as she gets done with her undergraduate studies. However, she is also getting married to a man her parents matched for her, within a year's time. "I have to get married. There's no question about that," says Farzana. "Even though I would like to work towards my own firm, I would never say no to a good match. Society would never shun me if I were both married and working."

In our society, women often suffer from the stigma that the recipe for being a successful career-woman involves being married. However, on the flip side of the coin, many women feel that being married holds them back, or rather, puts more pressure on them, thereby stunting their growth professionally.

Twenty-three-year old Rahima worked at an NGO as a programme coordinator. She often had to work long hours. When she got married, she found that this created a problem in her married life.

"My husband was very insecure because I had a very time-consuming job," says Rahima. "It has only been a year since we were married, but I have already quit my job. I had to. Before we were married he was so supportive and admiring about my job but now he says that a woman's place is to stay at home and I have no choice but to listen to what he says."

But do women really not have a choice? Twenty-four-year-old Samira recently got married to a doctor residing in the USA. Samira had to let go of a full-time job in the Human Resource Department of a very popular company in Dhaka, just so she could get married to a man she never knew and live in another country.

"I had to get married because I am not getting any younger, you know," says Samira. "It's hard to get a man if you reach the age of 25, and that's when you become a burden to your family."

"I think women allow their careers and lifestyles to be influenced by men and marriage," says Tupa, well-known model and choreographer, Binodon. "Instead of looking at marriage as a social institution, women should see it as something that we want to do. No one can put limitations on you unless you let them. Men shouldn't be in a position where they can tell you how to live your life. It will be hard for women to stand up for themselves and say no but they have to at some point because if they don't, they will lose their identities. We are not children so we need to stop giving in to social pressures. Women should stop seeing themselves as victims because that is the worst thing that they can do to themselves. You're a person, a human being, and you have a choice to say no when you want to and say yes when you want to."

Maliha has been married for over 25 years. She has three grown-up children and has been working in the development sector for almost 15 years. For her, economic stability and the power to be financially independent are key.

"I feel that there are two sides. Marriage provides social mobility to women in the sense that they can be less vigilant about following social norms basically because our society looks at them less critically. But this mobility doesn't necessarily translate into freedom unless there are certain economic, environmental and personal factors that go with it. One important thing is having economic freedom and one's own source of income and the ability to have the psychological strength to be economically independent. The moment a woman is economically dependant on a man, be it her father or husband, it obligates her to act in a certain way, and she feels that she has to repay her so-called debt."

Sometimes being financially independent does not always give you the clout that it should. Sayeeda and Sultana have both found that, after marriage, despite being financially independent and able to stand up for themselves and what they think is right, they have to deal with a lot of pressure from either their husbands or their in-laws to change their lifestyles and their ways.

Sometimes being financially independent does not always give you the clout that it should. Sayeeda and Sultana have both found that, after marriage, despite being financially independent and able to stand up for themselves and what they think is right, they have to deal with a lot of pressure from either their husbands or their in-laws to change their lifestyles and their ways.

"Before we got married, my husband used to love that I was so independent," says 26-year-old Sayeeda. "He loved that I had a set career path and was well-educated, had my own life, my own friends. After we got married, he became possessive, made demands, such as asking me to dress more conservatively, being more careful about what I did in public. He began to resent my job and always belittled me in public when I engaged in intellectual conversations. It's like he automatically became someone else when we got married. All his ideals and beliefs changed and he expected me to change too."

"My mother-in-law does not like the fact that I work," says 24-year-old Sultana. "Every time I leave in the morning for work, she makes a face. She tells my husband that she would rather I stay home and help around the house. At night my husband and I fight about it. He wants me to quit my job to bring peace within his family, but I refuse to do so. I have worked too hard to get where I am and I'm not giving that up, but sometimes I feel the pressure so strongly that I do want to give up, just out of sheer exhaustion."

"It's all about a man's security level," explains Maliha. "Most men -- especially in our society -- are scared that their wives will become more competent and successful. Men by nature are very vain and egotistical and it is hard for them to accept that their wives are more successful, or even successful to a certain point, so they start making boundaries and barriers to get in the way of a woman's success in her career. They get a kick out of the feeling and knowledge that they are the sole providers and protectors of the women."

Sometimes, unfortunately, the barriers are defined by a woman's family, rather than her husband or his family, and marriage is then seen as a way out, as is the case with 21-year-old Rima.

"After I got married, I was allowed to do all the things I was never allowed to do when I was living with my parents," she says. "I was allowed to further my studies, work full-time in a multinational company, wear whatever I want and go out without having to answer to anyone. It was like marriage was my ticket to freedom."

Often, however, women see marriage as that "ticket to freedom" and are cheated out of it regardless.

Says 30-year-old Tamanna, "I wanted to study medicine and become a doctor. When I got married, my husband and I moved abroad and I started to apply to med school. When I finally got accepted, he told me he would not allow me to attend because med school was too long a process and how would we be able to start a family and make a home if I was always studying and in school?"

According to Tupa, if the person you are to spend the rest of your life with cannot respect your needs, then it may be time to reconsider. "If the man in your life doesn't get it even after you sit down and talk to him and take your stand -- and the first few times it will be difficult -- but even if he doesn't get it after a while, then maybe he is not the right person for you, and you should have the strength to walk away for your own sake."

But is it so easy to walk away? Faustina Pereira, an advocate of Bangladesh Supreme Court and a director of Ain O Shalish Kendra, says that 'freedom' for a woman immediately translates to the ability to access the various structures and institutes of the State. This would encompass every facet of socio-legal interaction - from daily interactions in social and family life to participating in the highest level of State such as the Parliament. Pereira says that it is a vital mistake to see family life as something separate from State function.

But is it so easy to walk away? Faustina Pereira, an advocate of Bangladesh Supreme Court and a director of Ain O Shalish Kendra, says that 'freedom' for a woman immediately translates to the ability to access the various structures and institutes of the State. This would encompass every facet of socio-legal interaction - from daily interactions in social and family life to participating in the highest level of State such as the Parliament. Pereira says that it is a vital mistake to see family life as something separate from State function.

What about the legal system? How does it constrain women's freedom? The legal system we have inherited, says Faustina, is not elastic enough to yield necessary benefits to women in particular and men and women in general because it is steeped in a male perspective, and that too the male perspective of a particular class. "We now have an all-women police cell in Mirpur; but we must ask what necessitated such a cell?" asks Pereira. It shows that the whole system left by itself, starting from filing a GD to the investigation to the trial, cannot adequately address women's needs, thus necessitating such "special" measures for women.

Pereira says that the main problem is that the perspective from which our laws have been legislated and implemented, have never taken women to be the subject of law. "The male identity has always been the subject of law and written according to male needs," says Pereira, a human rights activist. "Most of the procedural laws have been written by a handful of British, white, upper middle-class men who had their own perspectives and whose perspectives found their way into the law." Women on their own rights were never made the subject of the law. The good news is that some laws are changing with the times, says Pereira. This is especially true for family laws regarding custody or payment of maintenance and dower - major factors that have kept many women in abusive or troubled marriages. When it is a question of giving up the children in order to be free from an unhappy marriage, women chose to stay just to keep the children. "What we must convince women," says Pereira, "is that they are not as vulnerable or helpless as they are made to think." She explains that, under the present custody laws, the court predominantly looks at what is in the best interest of the child and usually for infants and minor children, it is presumed that the mother, unless she is proven to be unfit, is the better custodian of a child in whose custody a child's welfare is ensured. She points out to judgements and precedents where it has been shown that religious laws on father's prerogative over a child is not immutable, and those laws will not influence the judicial mind if the court believes that the child will be better off with the mother.

According to Pereira, more and more middle-class and lower middle-class women have taken advantage of this law and have gained custody of their children. The legal guardianship of a child, however, still lies with the father, but, Pereira says that while we continue our advocacy to fight for mother's guardianship rights, we should build upon the strengths of mother's custodianship rights. As far as providing maintenance for the children is concerned, there is no way that a father can evade his responsibility. Muslim law in particular pays attention to the fact that the father is obligated to pay the maintenance of his children and the children's mother, even if she is divorced from him, has the right to demand this on their behalf.

Sometimes, even when there are no children, women continue to stay in abusive marriages because they feel they have nowhere to go. If they do not have the skills or education needed to get a decent job, this financial insecurity will be the biggest reason to endure a bad marriage. In some cases, a prenuptial agreement that the husband will provide financial maintenance in the case of divorce, gives women some security, although it is usually resisted at the time of the marriage. Women can claim past maintenance from her husband after divorce but not future maintenance.

So is 'freedom' an untenable dream? There is no obvious answer and a lot depends on the attitude of women themselves.

So is 'freedom' an untenable dream? There is no obvious answer and a lot depends on the attitude of women themselves.

"I think that real freedom is being able to make decisions about your own life based on reasons and feelings that you think are valid," says Zara. " It's perfectly normal to ask for advice or opinions from people whom you respect, but your final decision should be your own. Above all, you should be able to live your own life, provided you aren't deliberately hurting anyone, in the way that you want to, without everyone around you expressing an opinion about what you should do. One of the worst things in our society is the way that people feel that they have the right to pass judgement on others. They not only offer unsolicited opinions, they force them on you. And that is one of the hardest things about being a woman in our society - you are always subjected to the opinions of others, and made to feel bad simply because you don't fulfil whatever stereotypes they carry about how women should behave."

By equipping themselves with education, skills and the ability to support themselves, along with the determination to survive with dignity, they may not be guaranteed freedom. But at least they will give them a good chance to aspire for it.

Volume 4 Issue 36 | March 4 , 2005 |

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2005

Shreya is like any other 5-year-old - inquisitive, stubborn, experimenting, loves to rush out to the playground at class recess and hates to wake up for school early in the morning. However, for the last one year, Friday mornings have always been a special treat for Shreya. Now that she knows her numbers quite well, she gets someone to help her with the alarm clock, so as to wake up the next morning and catch Sisimpur on BTV at 9 am every Friday. “It's a wonder how hell breaks loose every time we try to wake Shreya up for school though,” says her mother Rahela Anjum, an executive working at a private company in Banani. Evidently, watching Sisimpur happens to be Shreya's top most priority at the moment. “My favourite character is Tuktuki,” she says, referring to one of the muppet characters featured in the show. “But I also like Halum since he can talk like a human and doesn't seem to scare anybody,” she adds talking about the tiger, yet another muppet character on Sisimpur.

Shreya is like any other 5-year-old - inquisitive, stubborn, experimenting, loves to rush out to the playground at class recess and hates to wake up for school early in the morning. However, for the last one year, Friday mornings have always been a special treat for Shreya. Now that she knows her numbers quite well, she gets someone to help her with the alarm clock, so as to wake up the next morning and catch Sisimpur on BTV at 9 am every Friday. “It's a wonder how hell breaks loose every time we try to wake Shreya up for school though,” says her mother Rahela Anjum, an executive working at a private company in Banani. Evidently, watching Sisimpur happens to be Shreya's top most priority at the moment. “My favourite character is Tuktuki,” she says, referring to one of the muppet characters featured in the show. “But I also like Halum since he can talk like a human and doesn't seem to scare anybody,” she adds talking about the tiger, yet another muppet character on Sisimpur.  Dr. Mahtab Khanam an eminent psychologist and consultant to the Sisimpur project has conducted various surveys and workshops with children and parents alike in several remote areas of Bangladesh. “Our community outreach programme works on raising the awareness amongst families regarding early life nurturing, health, hygiene and much more,” she says. “This is closely related to how we plan our concepts and scripts for every segment in Sisimpur.”

Dr. Mahtab Khanam an eminent psychologist and consultant to the Sisimpur project has conducted various surveys and workshops with children and parents alike in several remote areas of Bangladesh. “Our community outreach programme works on raising the awareness amongst families regarding early life nurturing, health, hygiene and much more,” she says. “This is closely related to how we plan our concepts and scripts for every segment in Sisimpur.” From top: Mohd. Parvez; Mir Syed Ali; one of the many visually impaired children at BMIS; Mitu and Asiya writing and reading Braille.

From top: Mohd. Parvez; Mir Syed Ali; one of the many visually impaired children at BMIS; Mitu and Asiya writing and reading Braille.

Manju Samaddar

Manju Samaddar Ansaruzzaman

Ansaruzzaman Mohd. Ismail Hossain Siraji

Mohd. Ismail Hossain Siraji N

N Nadia, with her children who love everything about Bangladesh

Nadia, with her children who love everything about Bangladesh Saira with her two sons-diehard Bangladeshi fans

Saira with her two sons-diehard Bangladeshi fans Saira- looks forward to the positive changes every time she visits home

Saira- looks forward to the positive changes every time she visits home Pamela, as a writer is fascinated by the country

Pamela, as a writer is fascinated by the country Mohammad Nurul Karim- always in touch with what is happenning in his homeland

Mohammad Nurul Karim- always in touch with what is happenning in his homeland Naimul- gets in touch with the Bangladeshi music scene this summer

Naimul- gets in touch with the Bangladeshi music scene this summer Sarah getting hands-on experience in journalism

Sarah getting hands-on experience in journalism Rabi- dabbling with development work

Rabi- dabbling with development work Rumana- getting some banking experience this summer

Rumana- getting some banking experience this summer

If attitude is an integral part of style then certainly Aneela Haque's designs have plenty of it. "I prefer my creations to stand out and show the right attitude," says Aneela, also owner of an advertising agency and a public relations and event management company. "I suppose that's what the people who walk into my store want as well."

If attitude is an integral part of style then certainly Aneela Haque's designs have plenty of it. "I prefer my creations to stand out and show the right attitude," says Aneela, also owner of an advertising agency and a public relations and event management company. "I suppose that's what the people who walk into my store want as well." Among the well known designers, Aneela Haque will be representing her own designs for the first time, representing Bangladesh this year at the three-day Bridal Asia event to be held at the Taj hotel in New Delhi from October 8-10. She will be unveiling, what she calls, "a poetic journal" where the "Majestic Royals by Aneela" will be displayed on the runway. "Travelling over the years has made me extremely sensitive to the cultural and social beauties of every country," she says. "There's something so beautiful in music, the art and the poetry that every culture represents. These art forms have a lot to say about one's own identity as a person as well. Every designer has his or her own character traits or identity marks clearly sprawled on the designs. One just has to look carefully at the clothes to know what exactly these characteristics speak of."

Among the well known designers, Aneela Haque will be representing her own designs for the first time, representing Bangladesh this year at the three-day Bridal Asia event to be held at the Taj hotel in New Delhi from October 8-10. She will be unveiling, what she calls, "a poetic journal" where the "Majestic Royals by Aneela" will be displayed on the runway. "Travelling over the years has made me extremely sensitive to the cultural and social beauties of every country," she says. "There's something so beautiful in music, the art and the poetry that every culture represents. These art forms have a lot to say about one's own identity as a person as well. Every designer has his or her own character traits or identity marks clearly sprawled on the designs. One just has to look carefully at the clothes to know what exactly these characteristics speak of."  Aneela has used jute-silk, a variety of cottons, khadi, muslin and crepe-silk for her designs. "My clothes have various scriptures and calligraphy on them," she explains. "Being someone who appreciates being global, rather than pointing down to a particular culture, I have tried to blend my own culture with bits and pieces of the ancient cultures from Egypt, Paris and many others."

Aneela has used jute-silk, a variety of cottons, khadi, muslin and crepe-silk for her designs. "My clothes have various scriptures and calligraphy on them," she explains. "Being someone who appreciates being global, rather than pointing down to a particular culture, I have tried to blend my own culture with bits and pieces of the ancient cultures from Egypt, Paris and many others."

Her brother, says Aditi, has it much easier, and can almost always get his way with their parents. "When I wanted to get a motorbike, my father wouldn't let me, because he didn't like it. But my brother managed to get his way."

Her brother, says Aditi, has it much easier, and can almost always get his way with their parents. "When I wanted to get a motorbike, my father wouldn't let me, because he didn't like it. But my brother managed to get his way." Sometimes being financially independent does not always give you the clout that it should. Sayeeda and Sultana have both found that, after marriage, despite being financially independent and able to stand up for themselves and what they think is right, they have to deal with a lot of pressure from either their husbands or their in-laws to change their lifestyles and their ways.

Sometimes being financially independent does not always give you the clout that it should. Sayeeda and Sultana have both found that, after marriage, despite being financially independent and able to stand up for themselves and what they think is right, they have to deal with a lot of pressure from either their husbands or their in-laws to change their lifestyles and their ways. But is it so easy to walk away? Faustina Pereira, an advocate of Bangladesh Supreme Court and a director of Ain O Shalish Kendra, says that 'freedom' for a woman immediately translates to the ability to access the various structures and institutes of the State. This would encompass every facet of socio-legal interaction - from daily interactions in social and family life to participating in the highest level of State such as the Parliament. Pereira says that it is a vital mistake to see family life as something separate from State function.

But is it so easy to walk away? Faustina Pereira, an advocate of Bangladesh Supreme Court and a director of Ain O Shalish Kendra, says that 'freedom' for a woman immediately translates to the ability to access the various structures and institutes of the State. This would encompass every facet of socio-legal interaction - from daily interactions in social and family life to participating in the highest level of State such as the Parliament. Pereira says that it is a vital mistake to see family life as something separate from State function. So is 'freedom' an untenable dream? There is no obvious answer and a lot depends on the attitude of women themselves.

So is 'freedom' an untenable dream? There is no obvious answer and a lot depends on the attitude of women themselves.